Chapter Seven

Developing Turkey

Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk) emerged triumphant in his war against the occupying powers. His government, established in Ankara, negotiated a new agreement, the Lausanne Agreement, effectively revoking the previous Sevres Agreement that had dismembered the Ottoman Empire. By 18 September 1922, the occupying armies were expelled, and the Ankara based Turkish regime, which declared itself the legitimate government of the country in April 1920, started to formalize the legal transition from the old Ottoman into the new Republican political system. On 1 November 1922, the newly founded parliament abolished the Sultanate, thus ending 623 years of monarchical Ottoman rule. The Treaty of Lausanne of 24 July 1923 led to the international recognition of the sovereignty of the newly formed “Republic of Turkey” as the continuing state of the Ottoman Empire, and the republic was officially proclaimed on 29 October 1923 in Ankara, the country’s new capital.

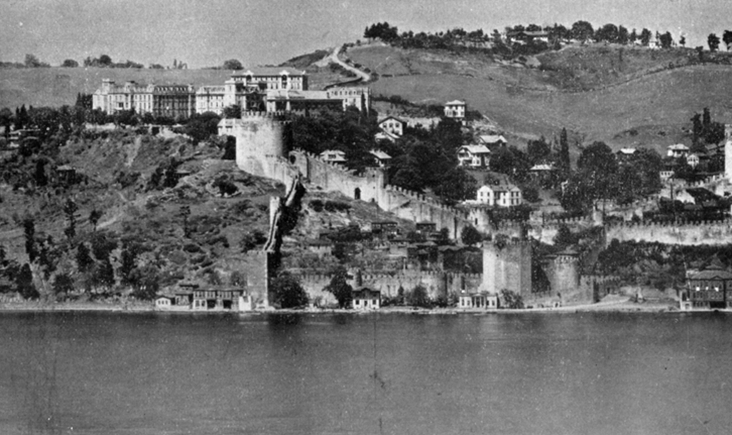

The same year, Dr. Rifat and his family moved from downtown Istanbul up the Bosphorus to a beautiful village called Rumelihisar. The family rented a wooden house and lived there until they moved to Ankara in 1932. I heard from my father that this house had later burnt down but I wanted to at least see where it might have been. Ekin abla’s mother Sevinç had mentioned that the family lived right across from “Ressam Şevket Bey Yalısı” (Painter Şevket Bey’s seaside mansion). I went to Rumelihisar and located a two story building on the waterfront that had a placket on its front wall. Going closer, I saw the writing on it: “Ressam Şevket Bey Yalısı”. Across from it, on the other side of the street, I saw a three-story building, sitting above an overgrown garden set on several levels. This building was obviously relatively new, but on two of the levels of the garden there were several holes on the old walls where there would have been beams for a wooden building. This was most likely where the family lived for nine years.

Rumelihisar housed a prestigious American school, Robert College, established by Protestant missionaries from New England. My grandmother registered her sons at this school. After all, as a young girl, she had attended the American School for Girls also set up by American missionaries. Nazire had even risked being caught by Sultan Abdulhamid’s spies, as the Sultan had forbidden Muslim girls to attend this school. My father reminisces in his memoir:

My mother took over now. She succeeded in registering both her sons in Robert College. We rented a beautiful house overlooking the Bosphorus, installed electricity and telephone and spent nine years there until I graduated with a B.S in Commerce in 1932. Robert College was founded in 1863. During the initial years, the greater number of the students consisted of Armenians, Greeks, Bulgarians and Jews. It was after 1923 that Turks began to turn up in sizable numbers. The services rendered by these colleges were immense. Instruction was in English, taught mostly by teachers from the New England area. After they graduated, students could enter American universities with flying colors. They were imbued with a healthy outlook and self-confidence, which led them to successful careers. (Faruk Kardam, unpublished memoir, 1986)

Robert College was founded by Cyrus Hamlin. Cyrus Hamlin, coincidentally, was also the seventh president of Middlebury College, my current employer. So many members of my family, my grandmother, father, brother, uncle, my cousins Ahmet and Ekin were educated at the American missionary schools in Turkey. I ask myself: Why were there American schools in the Ottoman Empire? It turns out that the American Board conducted missionary activities there since the early 1800s. It expanded its operations from the 1860s onwards particularly in Sultan Abdulhamid’s time. By the end of the Ottoman Empire there were more than hundred American Protestant Missionaries in Ottoman lands. The missionaries mostly tried to convert Eastern Orthodox Christians and Armenians. They focused on education and built good schools that offered science and languages. Would I be in the United States now if Cyrus Hamlin and other American missionaries had not once upon a time traveled to the Ottoman Empire lands? On the one hand, the missionaries were certainly furthering American values and interests. On the other hand, perhaps some of them were genuinely interested in helping people and probably had adventurous spirits.

According to Cyrus Hamlin, Robert College was founded as a Christian college but yet, it embodied a humanism open to all religions:

Establishing a Christian college in Turkey was then a doubtful and untried experiment. The probabilities of failure consisted in the division of Eastern populations. Religion had divided them into the Greek Church, the Armenian Church, the Roman Catholic Church, the Protestant Church, and among all of these are subdivisions, not tending to unity. There were Muslims and Jews. The spirit of race was also strong. The different nationalities composing the population of Turkey had preserved their separate existence, organization and national spirit with wonderful tenacity, under all governments, religions and systems, in pagan, Christian and Moslem times. These, it was said, will never unite in one institution of learning. To suppose it possible was considered to be absurd. But on the other hand, the East had made great progress towards Enlightenment. The old system of things was being broken up. There was more freedom of thought. There was a large element in Eastern society that rightly apprehended and esteemed freedom of conscience without being infidel. A Christian college which offered the best intellectual training and as broad a culture as our best New England colleges, could meet the wants of this class, of whatever race or faith…I considered myself more a missionary to Turkey than before. I was to labor, as far as possible, for all of its peoples, without distinction of race, language, color or faith. (Hamlin, 1878 republished by Elibron Classics, 2005, pp.285-86)

The years spent living in Rumelihisar and going to Robert College were special years for my father. As he reflects in his memoir:

Together with my brother Galip, we entered an unforgettable era of our lives. Robert College consisted of six large buildings: classrooms, laboratories, auditoriums, gymnasiums, dormitories and vast playgrounds. On the other hill, the College for Girls was, of course, another attraction. We had the system of sister classes allowing for gatherings, theater performances and even dances on the sly side. We were on the Bosphorus, overlooking the beautiful hills, the blue waters and the swift currents dividing the two continents. We managed to buy a small boat with a sail, and a racing bicycle in order to be on the move.

The summer vacations were fabulous: swimming, fishing, hiking and occasionally trying to attract the attention of the Armenian girls living in our neighborhood. Another entertainment feature was our friend Sadri. He was the goalkeeper of the soccer team, Beşiktash. He was the son of a black engineer and an Italian woman. Living in Rumelihisar and being a Robert College student, he had taken upon himself to teach us the latest dances: The Charleston and the Black Bottom. Being an excellent performer, he was always welcome at the two nightclubs in Bebek: the Muscovite and the Turquoise. When it suited him, he used to take us out to the clubs, and it must have been quite a sight to watch the young college students dancing with the White Russian émigré ladies.” (Faruk Kardam, unpublished memoir, 1986)

Russian emigre ladies? I recalled my sweet, white Russian piano instructor, Monsieur Sommer. I had heard about the presence of White Russians in Istanbul as I was growing up. It turns out that in November 1920, General Nikolayevich Wrangel, a White Russian commander, had sailed 126 ships into the Golden Horn, bringing more than one hundred thousand Russians (who were escaping the communist revolution) into the heart of Constantinople. According to Reiss, Constantinople’s theaters and nightclubs soon became a virtual Russian monopoly:

“The exiles ran clubs like the Black Rose and the Petrograd Patisserie, where the Russian waitresses were as much of a draw as the music, food or liquor (at Turkish restaurants only men were allowed to wait tables). The women were tall and fair-haired, and many were aristocrats, or said they were – thus at Le Grand Cercle Mucovite, a voguish restaurant, the waitresses were referred to as ‘duchesses’.” (Reiss, 2005: p, 113)

This all began to change as Mustafa Kemal overran the city in 1923. Constantinople’s years as a high living international capital were over. Two years later, Constantinople would be renamed Istanbul. Many emigres left as the Soviet representatives arrived. The Allied occupation of Constantinople would be mostly forgotten after the British left and the city belatedly embraced Mustafa Kemal. But the resentment that the Allies caused did not end, rather it became a part of the general Muslim resentment against the West.

While the boys attended Robert College, Dr. Rifat would board a boat from Rumelihisar to go to his office in Karaköy in the old section of Istanbul every day. The International Quarantine Service had been renamed ‘Istanbul and the Straits Quarantine Service’. Rifat was now tasked, along with two other colleagues, with its restructuring into a Turkish bureaucracy. In 1924, he was named the first Director General of this new Turkish bureaucracy. He was now a member of the modernizing elite of the new Republic of Turkey.

Rifat held this post until 1927 when Mustafa Kemal Ataturk ordered the directorate to be moved to Ankara. This was part of the plan to centralize all bureaucracy in Ankara, the capital. He objected to the order, pointing out that Ankara is in central Turkey with no access to coasts whereas the directorate had a mandate to monitor the traffic in coastal areas and assist refugees entering by ship. He offered his resignation. The Directorate eventually stayed in Istanbul, and in fact, I remember the present Assistant Director, telling me that my grandfather was responsible for this outcome and that he and other staff members were grateful to him.

My grandfather began to suffer from anxiety and depression during this period. According to one of his biographies, he was allegedly afraid that he might not succeed in overseeing the transformation of the International Quarantine Service into a Turkish bureaucracy. (Erdem, 1948) This may well be the case as the French who were running the Service left the country with money from its coffers, know-how and resources. But for a successful long term bureaucrat, could Rifat be phased by this assignment to the point of depression? Or was there something else?

I return to my father’s memoir for answers. He writes:

“My father had no business experience. When the reserves of the International Quarantine Service were liquidated, he received a lump sum of 23,000 Gold Liras which were 20% higher than paper money. We could have acquired two apartment houses, eight flats each, with this money which would have provided us with security for the rest of our lives. Two shrewd operators from his hometown of Kilis approached him and led him to an investment in a joint venture. That was the last he saw of that money. After eight years of litigation, the 2000 TL he collected did not even cover his legal expenses. This was a heavy blow on him, which he could not wipe off his memory until his dying days.” (Faruk Kardam, unpublished memoir, 1986)

Rifat, who had proudly called himself ‘Kilisli’ (from Kilis) all his life and welcomed all visitors from Kilis to his home, was betrayed by his own town folk, perhaps even by members of his own family. His brother’s biography reads:

“Rifat liked his town folk so much that he would welcome visitors from Kilis with excitement and happiness. He asked them news of Kilis, and recounted his childhood stories to them. He always tried to help people from Kilis in any way he could. He carried the name “Kilisli” with such pride and owned it that some of his friends and acquaintances just called him Kilisli.”(Mehmet Emin Bilgen, Dr. Kilisli Rifat’s Biography, unpublished document)

I imagine that my grandfather must have been heartbroken. He must have started questioning himself. Should he have used greater discretion? Been more careful? How could he not see this coming? He had worked so hard to make sure his family would be comfortable and secure after his passing away. Now what? This deception must have devastated him, especially given his commitment to integrity at all cost.

SHAPING HEALTH POLICY, CREATING NEW CITIZENS

Dr. Rifat was now spending long days at the courts, with lawyers, suing the people who swindled him. Meanwhile, he served as a Professor of Public Health and Hygiene, as well as the in-house physician for the Faculty of Social Sciences (Istanbul Mülkiye Mektebi) until it was moved to the capital, Ankara. He returned to his passion, to teaching. His peers lauded his teaching ability. In an article on Dr. Kilisli Rifat, Şehsuvaroğlu comments:

Many classes that needed to incorporate experiments and practical knowledge did not. Students learned theories but did not practice what they learned. Dr. Kilisli Rifat’s classes were an exception. He brought to class items such as a sheep’s brain or heart so that students could practice what they learned. Rifat always came to class with a smile, was well organized and clear and interesting lectures. Students looked forward to his classes with enthusiasm. (1971, p. 2)

He published many articles on hygiene, public health, eugenics, theories of natural and social evolution, on race and on international relations until he died in 1936. He also translated two books from French including “Sex Education for Young Men” and “How To Stay Young”. His articles place him largely within the mainstream of his generation of medical doctors who shaped the new health policy of Turkey. At the time of Turkey’s founding, the educated elite constituted a small percentage of the population and doctors were considered important members of this elite. In fact doctors emerged as one of the most salient, self-appointed groups who tasked themselves with creating the citizens of this new country. They considered themselves not just doctors but intellectuals, writers and policy makers. Güvenç-Salgirli (2010) writes that doctors in this era were mainly concerned with establishing themselves as the ‘intellectual aristocracy’, more than practicing medicine for the people and public health.

Turkey in the 1920s was in a state of devastation. There were significant economic and demographic shortages. Communicable diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, trachoma, gonorrhea, syphilis were rampant. Mustafa Kemal and the elites concluded that the population had to be educated with a modernist vision and that health education had to be the priority. Eugenics, popular in Europe, became an inspiration to the Turkish elites. Eugenics is a set of beliefs and practices aiming to improve the genetic quality of the human population. It is also a social philosophy advocating the improvement of human genetic traits through the promotion of higher rates of sexual reproduction for people with desired traits or reduced rates of sexual reproduction and sterilization of people with less desirable traits. Accordingly, prostitutes and alcoholics were considered to be the carriers of ‘social diseases’, which threatened the future of the Turkish race. Some went as far as recommending forced sterilization of those people with communicable diseases. Intervention was considered necessary, not just in usual suspects of eugenics, but also regarding the remnants of Ottoman aristocracy, degenerates, bohemian artists, and the newly rich. Eugenics became a matter of keeping Istanbul ‘clean’. In short, it was believed that social intervention was necessary in order to create ‘the new Turk’.

The emphasis on social policies naturally reflected the health concerns of war: “The application of social policy in this period was composed of struggle against epidemics, preventive health policies primarily for the army, and then the people, and taking care of war orphans”. (Ilikan, 2006, p. 41) These policies eventually proved successful. Maternal mortality decreased, the incidence of communicable diseases declined.

An underlying assumption of eugenics was that in nature, natural selection allowed those that were the fittest to survive but in society, social selection did not work as well. Societies and individuals that were weak, sick and lacked various capacities continued to survive, preventing the ‘best’ to reign, thus the need for eugenics, the science of creating and reordering society. The objective of eugenics was to produce well-bred generations. Considering that during this period sexually transmitted diseases and epidemics like tuberculosis were rampant, many countries, including the United States and Sweden, took on the task of ‘creating’ a new healthy generation. This meant that the diseased people or people at risk because of their heredity had to be somehow separated from the healthy ones. It also meant that public health education had to become a priority. Turkey followed this global trend.

The future of the Turkish race was defined in terms of the development of good morals and habits of hygiene. As Dr. Rifat pointed out in one of his articles:

“Ignorance and laziness are the main causes that harm one’s health and the only way to combat them is with a strong propaganda. One must encourage people to lead a healthy life in their apartments, teach them habits of cleanliness and preventative health. Due to lack of moral education and of carelessness, few listen to such advice. Ignorant people tend to be against any innovation, and fail to adapt. These faults must be overcome.” (1931A, p. 6)

He drew from Health Ideals in America (A college text book of Hygiene, Franklin Smiley and A. Gordon Gold, New York, Macmillan. 1928) on how to achieve ideal health:

- Work for eight hours a day every week, without worry, nervousness or being tired.

- Eat three healthy meals a day

- Sleep eight hours every night without interruption

- Enjoy social interaction with others for one hour a day.

- Be involved in something creative, such as music, art, or theater two hours a day.

- Trust yourself, avoid being fearful, love your work and expect to be successful and enjoy at least some success, be ambitious and enthusiastic. (1931A: pp. 6-8)

Health education, he wrote, should include advice on how to choose one’s spouse. Learning to choose the right spouse involved making sure that the spouse has a clean lineage (no alcoholism, drug addiction or venereal diseases in the family). It also involved getting certificates of good health before marriage. Rules of hygiene were furthermore considered a way of teaching good manners and producing well-bred individuals. (1931B)

Dr. Rifat stopped short when it came to forced sterilization. Instead, he suggested that every person who plans to get married should first be tested for any kind of communicable disease and if found to have such a disease, should not be allowed to marry until the disease was under control:

“The point for a certificate of health before marriage is: 1) to increase the number of marriages, but 2) to only allow those who are healthy and who are likely to produce healthy children to marry. Those people who intend to marry must show such a certificate to the official marrying them. Such a stipulation should become a law. If one or both partners have communicable diseases, they should not be allowed to marry until they are healthy. We should protect children who come to this world from thoughtless parents. There are some objections to this proposal. Doctors say that they will have to disclose their patients’ private lives, but they already have to do this with military medical examinations. Another objection is that people will start living together without marrying to avoid this examination. This problem will not be solved as long as doctors just sign off without even examining patients. Both the doctors and those who are getting married should be in agreement that this is an important responsibility; otherwise, there will be no solution. “ (1931B: p. 10)

According to Dr. Rifat, the solutions to overcoming communicable diseases, particularly sexually transmitted ones, lay in the health and moral education of young men. He translated a book from French, written by Dr. A Calmette, titled “Sex Education for 15 Year Old Males”. This book discusses how young men should be taught to avoid prostitutes. Rifat points out that some people object to sex education as they may find it immoral. He argues that what is really immoral is to hide truths and perpetuate ignorance. Young people should not graduate without having learned sex education and the moral and physical aspects of sex. They should be at least aware of ‘dubious’ kisses and, being involved with women who are having their period or with prostitutes 30% of whom have syphilis. According to Rifat, sex education should be one of the top policy priorities. Conferences, movies, workshops, and public campaigns must all be employed to focus on sex education. Interestingly, he advocated sex education for men and good morals for women.

He viewed women’s morality of utmost importance in preventing sexually transmitted diseases:

“The causes of diseases such as syphilis, cancer or tuberculosis are our own ignorance, and lack of attention to health rules. We overwork our nerves and our reproductive organs. We are not aware of how much strength we have, and women are full of insatiable desires. As a result, both families and entire races can become weak, both bodily and mentally. The only way to avoid such results is a strong sex education. Syphilis is more prevalent among workers than peasants or the city dwellers. But there is nothing shameful about contracting syphilis. It is, however, a terrible illness because it is easily contractible, and it affects children.” (1933B, p. 20)

He pointed out that children born to women with syphilis constitute a great threat. Thus he concluded that the power of a nation doesn’t rest in its laws and legal system, but in its women’s virtue and education.

What to do about prostitution? Rifat argued that sexually transmitted diseases could not be prevented just by legal means and pointed out that communicable diseases were substantially reduced in Sweden, Norway, Holland and Denmark because they stopped controlling prostitution by legal means. Attempting to control prostitution by law keeps prostitutes away from dispensaries and tests and thus increases the potential of sexually transmitted diseases. Also, there are many women, he argued, who don’t have a legal license for prostitution but engage in it anyway. Instead of collecting prostitutes from streets and declaring war against it, why not assist them by finding other means of employment for them? He believed that the most important solution is not in police action, but in preventative health education.

He asked: Why is there prostitution in the world? As long there are wars and large military forces and as long as military life involves a single life for men, it is going to be difficult to overcome sexually transmitted diseases. His proposed solutions include a requirement of clean health certificates before marriage, establishing special courts and detention houses, prohibiting illicit medicine that is supposed to cure syphilis and prohibiting books that encourage people to commit adultery and promiscuity. Instead of running contests and rewarding families who have the highest number of children, Rifat suggested that the government policy should be directed towards educating the public. (Dr. Kilisli Rifat, 1933B)

Rifat was also concerned with increased drug use. He was worried about the increased number of people selling and using drugs and insisted that it is a social responsibility to protect and help to cure those that are addicted. He claimed that advanced civilization has led to excesses and that addicts need to be saved by opening special houses and dispensaries for them:.

“Any addict should be admitted to such places upon the request of their families or the government. On the supply side, we need to fight narcotics through laws, by prohibiting their sale and punishing those that are selling them. Furthermore, public campaigns, for example in movie theaters, showing the terrible states of addicts would be very useful. If a famous person sponsors such a campaign, it would be even more influential.” (1933A, p. 21)

Dr. Rifat’s report on the resolutions of a United Nations Rural Development and Hygiene conference held in 1931 is eerily reminiscent of the conclusions of modern day United Nations conferences on Development. The principles of rural development are outlined in one of his articles as follows: (1932, pp. 33-34)

- Provision of medical assistance and establish medical teams to work in rural areas

- Provision of drinking water

- Prevention of malaria

- Curriculum development promoting public health

- Training of female health workers and engineers for work in rural areas

- Access to clean water and basic sanitation;

- Agricultural development

- Building appropriate housing

He pointed out that successful rural development depends on:

- Promoting economic efficiency

- Adaptation to local conditions

- Participatory development and collaboration

- Capacity building of rural development practitioners and bureaucrats

- Promoting village development through education, financial and technical assistance

- Appropriate incentives

- Decentralization of rural development over time, to encourage non-governmental and voluntary organizations to get involved in the development of villages.

A synthesis of the above articles reveals that Dr. Rifat was concerned with development issues that are still vital today. He recommended training and employing women health workers in villages, establishing sanitation programs, access to clean water, providing appropriate housing and engaging in participatory rural development, including collaboration with non-governmental organizations. These are still central issues in development after almost a century. He believed in the importance of sex education for young men when sex was a taboo subject. In the early 21st century, the need to educate men in gender based violence, in combatting diseases like AIDS, is finally being recognized, so is the importance of girls’ education. While Rifat was in favor of educating women and girls, he reserved ‘sex education’ for men and ‘virtuous behavior’ for women. He offered multiple approaches to deal with prostitution and drug addiction both on the demand and supply sides: offering alternative employment to prostitutes, making sex and health education more widely available, opening healing centers to drug addicts, fight narcotics with laws to reduce supply.

ARE SOME RACES BETTER THAN OTHERS?

With the rise of Nazism and Fascism, a new discipline called anthroposociology was born in the period between the two World Wars. This new discipline assumed that human races differed in terms of character and intelligence and that some races were better than others. Another assumption was that intelligence could be measured by brain size. Dr. Kilisli Rifat agreed with his contemporaries that the development of a race is contingent upon the development of the brain, its weight, width, length, and other measurements. He also agreed with his contemporaries that Caucasian races had more highly evolved brains than others, and that men are more intelligent than women as the latter’s brain sizes are larger.

“A male brain is four times wider than a monkey’s brain. Brain width changes according to races so that Caucasian brains are at the top. It also changes according to gender, so that the width of the brain is wider in males than females. “ (Dr. Kilisli Rifat, July 1934: p. 13)

How did Dr. Rifat view different races? First, the discussion of race must be put in its historical context. ‘Race’ had a different meaning then. It was a term that incorporated words like nation, group, ethnicity, society and others. For example, race in Turkey at that time was understood to be inclusive such that the Anatolian race included Turks, Kurds, Jews, Armenians and others. Dr. Kilisli Rifat wrote: (August 1934, p. 14)

“Different races come into being in different climates. In terms of intelligence, every race has acquired certain characteristics based on their interests, history and locale. Every race tends to congregate around a leader or a group of leaders who are considered most powerful and intelligent. Hierarchy, respect, justice and morality constitute the basis of every nation, and nations have come into being in this way.”

He went on to investigate characteristics of different races in terms of their psychological and social characteristics: (Dr. Kilisli Rifat, July 1934, pp. 14-15)

“Races possess particular social characteristics, as well as spiritual and intellectual attainments. For example, there is a Protestant spirit. Due to the cruelty Protestants have suffered from, one detects a certain spiritual oddity. They are very serious, rational and levelheaded, which prevents them from making mistakes. At the same time, as they became richer, protestants have become a little more relaxed, thus making them more attractive and easier to get along with.

Semitic races have suffered from horrible cruelties. In order to buy their safety and security, they had to look for ways to become rich. Their suffering has made them physically weak, but strong in accounting and in manipulation. They started to manifest themselves like an aristocracy in intelligence and wisdom. Some Jewish people have an extraordinary desire to acquire more goods but this will disappear over time as they become freer. Jews know how to be attractive, how to be well-liked, as well how to rule. If they could rid themselves of the insecurities that pervade their whole race, they could be very valuable to humanity.

Muslims are always free, they are conquerors. Arabs hate commerce. They are not greedy. They are in love with love. They love poetry, music and sports and have developed these further. In contrast, the spirit of black people is poor. Their spiritual life is simple. A black person is like a child at every age, s/he is changeable, superficial, and impulsive. They don’t have many abstract thoughts, and even if they do, these thoughts, are devoid of originality. The Japanese feel the insecurity of the land they live on. They have equanimity, yet they are constantly worried. The Orthodox Christians are conservative and thus, the adherents’ spirits are not expanded or enlightened. Perhaps Bulgarians and Greeks constitute an exception. Greeks are pretty similar to Jews.”

According to Rifat, the psychology of race is about the investigation of the thoughts and emotions that shape a race. Today one might call these thoughts ‘the collective consciousness of a group of people’. Sometimes the races themselves may not be aware of their own physiological and psychological states.

What is a nation? Rifat’s answer is that a nation is a group of people who have assimilated into a whole in a harmonious way, with pride in their race and history. Every nation’s psychology is dependent on its political spirit, its laws, and its economic and disciplinary state. (Dr. Kilisli Rifat, July 1934, pp. 15-17)

“The psychology of Catholic nations: These nations are open, free and have a roguish sensitivity. The manifestation of this psychology is overflowing in the Spanish and Italians. It is balanced in the French and the Belgians and harmonious in the Austrians. Climate and form of government have taken away the sheer physical force and stubbornness and have given them a special kind of attractiveness. Therefore, there may be different psychological tendencies in the same country. For example, the people in Normandy, France are likely to be hardworking, steadfast and enduring. The people in southern France, on the other hand, tend to be artistic, simple, sensitive, and love to entertain.

When confronted with danger, the brain in Italy responds with attention to minute details, in Spain and Austria with roughness and apprehension and at the Tuna (Danube) river, with arrogance and self-importance. Germans are slow in understanding, but they are rule bound and thoughtful. They have a strong sense of organization, and they have great powers of endurance. Self-possessed, rarely under threat themselves, they can be a threat to others instead, and even though they are appreciated for their prowess in business, they are overly proud. This excessive pride can be hazardous to their spiritual well-being. The Swiss and the Dutch have also acquired these characteristics without questioning them.

The British are egotistical. Their country’s tough climate has endowed the British with condescension and indifference. The British are shrewd and conniving. But if they receive respect towards their vital interests, they exhibit a noble virtue. The Americans don’t have great tact, but they have created a new nation that is attached to affluence and to trade. They are hard working and easygoing. Americans want to go straight to their objectives. They want to achieve results; they are brave, enterprising and successful. They differ from the British and the Latins by their simplicity. Like all young nations, Americans are emotional, virtuous and impulsive.”

It was important for Dr. Rifat, as was for other intellectuals in Turkey of his time, to show that the Turkish race was important and to be respected. So he argued that civilization sprung from the heart of Anatolia:

“Human life most likely started in Asia Minor and Palestine since the climate is very moderate and conducive to the development of human intelligence and civilization. This happened seven or eight thousand years before the start of the Christian calendar. Arthur Gobineau, in his book called The Inequality of the Human Races, 1834, has acknowledged the high level of evolution of those people originating from Asia Minor (today’s Turkey).” (Dr. Kilisli Rifat, June 1934: p. 34)

Are all races equal? Is there one best race? Can a best race ever be created? Rifat had some reservations about this question: (Dr. Kilisli Rifat, June 1934, pp. 13-14)

“Races are not equal in terms of their evolution. Climactic factors influence heredity. Due to climactic differences, ‘ethnic genes’ emerge. For example, one race may be prone to rationality and even temperedness, another to imagination and fantasies. Races are not strictly separate from each other by clear lines, but, in fact, their characteristics may merge into each other. They are like the richer or poorer children of the same family.

The science of natural selection has begun to classify some races as higher and others lower. For example, colored people are considered to belong to lower races. In my view, colored people should not be discriminated against. This is a myth. They will no doubt become elevated in the future. No one has the right to diminish one race in order to elevate the other.

Natural Selection theories claim that white races, which are physically and mentally powerful, should mix with each other. This is because good traits pass on from generation to generation. We can understand why natural selection theories are favored since their objective is to bring forth people with the best traits and ferret out or eliminate those with weaknesses.”

He concluded with two basic reservations about policies inspired by eugenics: 1) Promoting the rise of high intelligence may result in fatigue over time and this may lead to undesirable consequences. 2) Overspecialization may, over time, lead to a decreased capacity for adaptation. In short, Rifat claimed that we should not exaggerate natural selection and that civilizations have their own life span: (Dr. Kilisli Rifat, July 1934, p. 18)

“On average, every civilization lasts about 1000-1500 years. After this period, a civilization shows signs of fatigue. Just like a land that receives the same seed over and over again, subsequent generations become less and less handsome and strong. At some point the land needs to be rejuvenated. Just like the soil, a civilization doesn’t get destroyed, it simply changes shape and gets reformed. Chinese and Persian civilizations have lasted a thousand years. So have Greek, Roman and Jewish civilizations. It seems that white races are especially prone to develop the power of the mind. It is important that in a civilized continent, the number of people from the backward races should not be so high as to overpower the rest and impose their habits and traditions.”

Why do civilizations grow old and die? Rifat gives the following explanations: (Dr. Kilisli Rifat, August 1934, pp. 7-11)

- Economic reasons: If people cannot sustain themselves and find employment. This results in out migration and the dissolution/dissipation of a nation.

- Moral reasons: If development of a civilization is fast and violent, so is it fall. An arrogant elite takes over and sets up an oligarchy. The masses are ignored and feel stuck, and they don’t have the opportunity to mature. They no longer have the ability to renew the elites who rule.

- The influence of genius: Races that develop fast and are highly developed can become fatigued. There is a high cost to progress.

- Mediocrity

- Equality: A major manifestation of advancement is equality. As equality increases, ambition and entrepreneurial spirit declines.

- Decline in fertility

- Corruption, tolerance for lies, immorality and the pursuit of pleasure

- Feminism: In the nations where pro women ideas dominate, fertility begins to diminish leading to a decline.

He then went on to analyze the different nations in terms of where they are in their life span. Italy, England, France, Spain and Portugal are old nations, while Germany, Russia and the United States are young. The young nations have the power to develop a ruling elite and rise higher. He claimed that China will wake up and, with appropriate discipline and organization, become one of the most powerful and developed nations of the world. Yellow races, if they are not prevented by Russia or the United States, are likely to dominate the world. So Rifat thought that Europe was being threatened by yellow and black races and that only white races were fated to progress furthest as human beings. (Dr. Kilisli Rifat, August 1934: pp. 8-14)

Rifat argued that successful nations had benevolent dictators who encouraged the development of a specialized elite. Such an elite should be able to agree with each other in a ‘manly’ manner and be able to implement a proper division of labor. He believed that this type of dictator could only emerge as a result of chance or a revolution. After all, the interwar period was marked by the rise of two dictators, Hitler and Mussolini, both of whom had a strong influence on Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and his followers. Of course, Mustafa Kemal himself was such a ‘benevolent dictator’. (Dr. Kilisli Rifat, September 1934: p. 9)

Dr. Rifat tackled the popular ideas of eugenics and natural selection in his articles. At times, his arguments were contradictory. On the one hand, he agreed with his contemporaries on the supremacy of white races and made sure that the Turkish race was included in this category. Yet at the same time, he argued that nobody had the right to elevate one race at the expense of diminishing another. (Dr. Kilisli Rifat, April 1934, p. 26) He claimed that women’s brain sizes are smaller and therefore they are less intelligent. He was against ‘feminism’ and believed that ‘the domination of women’ will lead to a decline in fertility. Yet, he also advocated women’s education and employment. Ultimately, he was adamant that natural selection theories must not be exaggerated, arguing that ‘balanced’ races were more successful over the long term. (Dr. Kilisli Rifat, April 1934, p. 26)

(c) Nükhet Kardam 2015

Click here to purchase the entire e-book in Kindle format.

References and Credits

http://www.boun.edu.tr/en_US/Content/About_BU/History/Photo_Gallery

Erdem Fethi, Türk Hekimleri Biyoğrafyası, (Biographies of Turkish Doctors), Istanbul, 1948.

Güvenç-Salgirli, Sanem, “Eugenics for the Doctors: Medicine and Social Control in the 1930s in Turkey”, Journal of the History and Medicine of Allied Sciences, 2010, pp. 1-32.

Hamlin, Cyrus, Among the Turks, Elibron Classics, 2005 (Originally published in London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, 1878).

Ilikan, Ceren Gülser “Tuberculosis, Medicine and Politics: Public Health in the Early Republican Turkey”, unpublished MA thesis, Boğazici University, 2006.

Dr. Kilisli Rifat, Verem Kabili Şifadir (Tuberculosis is Treatable), Foreword by Besim Ömer Pasha, Istanbul, 1905.

Dr. Kilisli Rifat, Umumi Hıfz-ı Sıhhat, (Public Hygiene), Mekteb-i Mülkiye Matbaası, 1908.

Dr. Kilisli Rifat “15 yasindaki Genc Erkeklerin Tenasül Terbiyesi,”(Sex Education for 15 Year Old Males) translated by Dr. Kilisli Rifat from Dr. A. Calmette, Istanbul Askeri Matbaa: 1930.

Dr. Kilisli Rifat, “Sihhat Ideali” (Ideal Health), Mülkiye Mecmuasi, No. 3, Haziran 1931A.

Dr. Kilisli Rifat, “Evlenme Sihhat Raporu” (Health Report for Marriage) Mulkiye Mecmuasi, No. 6, September 1931B.

Dr. Kilisli Rifat,”Hastahanecilik ve Köycülük” (Hospital Building and Village Health), Mülkiye Mecmuasi, No. 11, February 1932 (19-21).

Dr Kilisli Rifat, “Keyf verici Zehirler Iptilasi’, (Addiction to Narcotics), May 1933A, No. 26.

Dr. Kilisli Rifat, “Ictimai Hastaliklardan: Frengi” (Communicable Diseases: Syphilis) November 1933B, No. 32.

Dr. Kilisli Rifat, Normal Doğuş – Istifa ve Veraset (Natural Selection), Mülkiye Mecmuası, February 1934, Part One.

Dr. Kilisli Rifat, Normal Doğuş – Istifa ve Veraset, (Natural Selection) Mülkiye Mecmuası, April 1934, Part Two.

Dr. Kilisli Rifat, “Irk ve Insan” (Race and the Human Being), June 1934, No. 39 Birinci bolum (Section One).

Dr. Kilisli Rifat, “Irk ve Insan” (Race and the Human Being), July 1934, No. 40 Ikinci bolum (Section Two).

Dr. Kilisli Rifat, Milletlerin Ihtiyarlığı ve Ölümü, (The Maturity and Death of Nations) Mülkiye Mecmuası, August 1934, No 41.(Section One)

Dr. Kilisli Rifat, Milletlerin Ihtiyarlığı ve Ölümü, (The Maturity and Death of Nations) Mülkiye Mecmuası, September 1934, No 42. (Section Two)

Dr. Kilisli Rifat (Kardam), Genç Kaliniz (Stay Young), translated from Victor Pauchet, Ankara, Recep Ulusoglu Basimevi: 1939.

Reiss, Tom, The Orientalist, New York: Random House, 2005.

Şehsuvaroğlu Bedii, ‘Hekim ve Hakim Olanlar’, (Doctors and Philosophers), Yeni Asya, Year 1 No. 344 February 1971.